March 1911: The End of the 1911 Legislative Session and Next Steps for Woman Suffrage in Oregon

By December 1910 Oregon suffragists had had collected enough signatures by the initiative petition process to place the measure on the November 5, 1912 ballot. Suffragists requested that the Oregon legislature, meeting in January and February 1911, give its support to the equal suffrage ballot measure. Legislators passed Senate Joint Resolution 12 on February 17, 1911.

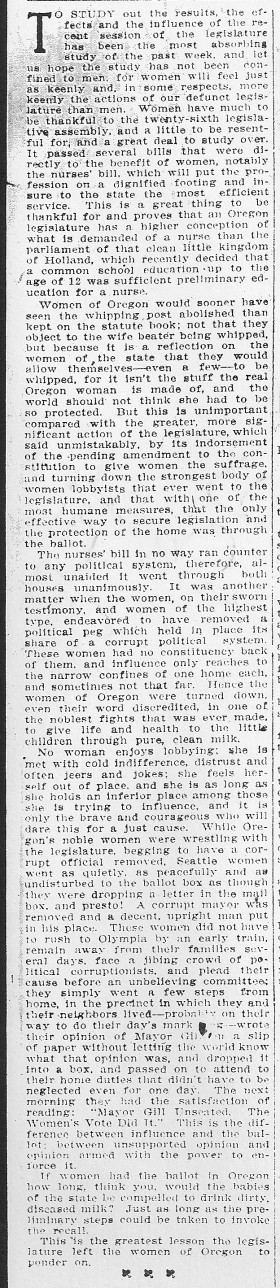

In March suffragists would begin the sixth campaign for votes for women in the state. Activist Sarah A. Evans had this in mind as she reviewed the lessons of the legislative session in her weekly Women’s Clubs column for the Oregon Journal (February 26, 1911, 5:7). Washington women had achieved the vote in 1910 and were using it; Oregon activists looked to November 1912 as the year of victory.

Evans counted several gains. One was legislation establishing the Oregon State Board of Nursing and another was the end to Oregon’s controversial whipping post law for men convicted of domestic violence. But for Evans, the recent legislative session provided a strong lesson about the need for woman suffrage.

The “strongest body of women lobbyists that ever went to the legislature,” she wrote, failed to convince the Oregon legislature to pass a statewide pure milk law. Portland women, led by Esther Pohl, Evans and a coalition of activists, had passed several progressively stronger city ordinances for pure milk. In 1911 they hoped to remove state Dairy and Food Commissioner J.W. Bailey and pass a statewide bill. Governor Oswald West asked the legislature to investigate and women testified before a joint house and senate committee. The failure of this bill, for Evans, proved that women without the vote, even though working actively in the political process through coalition building and lobbying, could not hope to effect political, social and economic change in a significant way.

“Influence,” she wrote, “only reaches to the narrow confines of one home each, and sometimes not that far.” Suffrage supporters like Esther Pohl Lovejoy joined Evans in calling for the vote to achieve what “influence” could not.

Evans also provided a perspective on what lobbying was like for women in 1911 before the achievement of woman suffrage. “No woman enjoys lobbying: she is met with cold indifference, distrust and often jeers and jokes; she feels herself out of place and she is as long as she holds an inferior place among those she is trying to influence, and it is only the brave and courageous who will dare this for a just cause.” Oregon women, she wrote, were “wrestling with the legislature.”

She contrasted this with the recent action by newly enfranchised Seattle women to recall Mayor Hiram Gill, whom they felt was not addressing gambling and prostitution in the city. Seattle women, she wrote, “did not have to rush to Olympia by an early train, remain away from their families several days, face a jibing crowd of political corruptionists, and plead their case before an unbelieving committee” as Oregon women had just done in Salem. They went to the polls and voted.

For Evans “this is the greatest lesson the legislature left the women of Oregon to ponder on.”

Sarah A. Evans, “Women’s Clubs,” Oregon Journal, February 26, 1911, 5:7

—Kimberly Jensen

Further Reading:

David Peterson Del Mar, “His Face is Weak and Sensual”: Portland and the Whipping Post Law,” in Women in Pacific Northwest History ed. Karen J. Blair, rev. ed. (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1988): 59-89.)

John C. Putnam, Class and Gender Politics in Progressive-Era Seattle (Reno: University of Nevada Press, 2008

Shanna Stevenson, Women’s Votes, Women’s Voices: The Campaign for Equal Rights in Washington (Tacoma: Washington State Historical Society, 2009)

Want to read more articles from Oregon suffrage campaigns? Click here

Permalink