January 1912: First Meetings of the Suffrage Year

January 1912 was a very active time for suffrage organizing in Oregon. Suffrage workers wanted to gain the vote and worked to establish organizations that would speak to specific groups of male voters.

That month several vital organizations formed: the Men’s Equal Suffrage Club, led by lawyer William M. “Pike” Davis; the Portland Equal Suffrage League, organized by Josephine Hirsch; and the Portland Woman’s Club Suffrage Campaign Committee led by Esther Pohl Lovejoy, Sarah A. Evans, Elizabeth Eggert, and Grace Watt Ross. The Oregon Federation of Labor endorsed woman suffrage with a unanimous resolution and the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union lent its support to the cause.

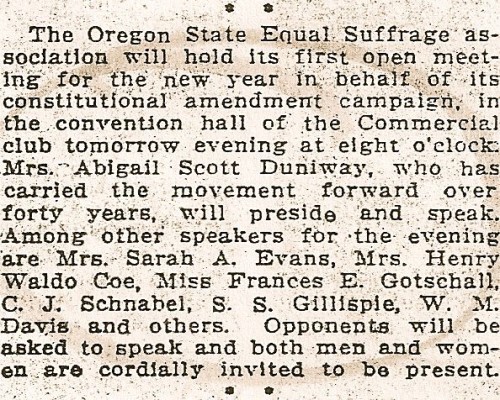

The Oregon State Equal Suffrage Association had weathered many storms; it’s leaders would continue to organize across the 1912 at the same time that these other groups worked for the votes for women cause. The group held its first meeting of 1912 on January 24. Abigail Scott Duniway presided and a cross-section of suffrage leaders spoke. “Opponents will be asked to speak,” the Oregon Journal noted, “and both men and women are cordially invited to be present.

First Meeting of the Oregon State Equal Suffrage Association for 1912, Oregon Journal, January 23, 1912, 12.

Want to read more articles from Oregon suffrage campaigns? Click here

Permalink

December 1911: “Leap Year is Coming”

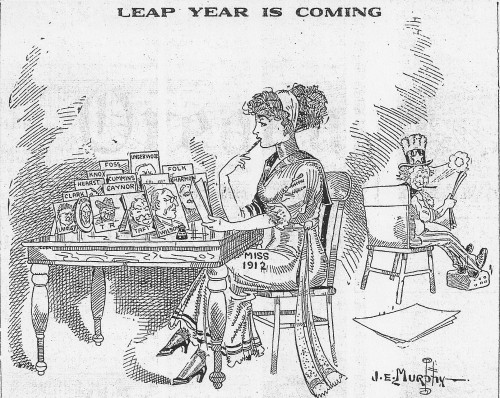

Editorial cartoons in city newspapers provide a window onto some of the feelings and reactions cartoonists, editors and readers had about woman suffrage. On December 16, 1911 cartoonist J.E. Murphy published “Leap Year is Coming” on the front page of Portland’s Oregon Journal

J. E. Murphy, “Leap Year is Coming,” Oregon Journal, December 16, 1911, 1.

The year 1912 was a “leap year,” giving February a 29th day. Popular tradition held that in leap years women could ask men to dance or to marry, unlike other years when they were not to take the lead.

J.E. Murphy used this concept of a leap year as a foundation for his editorial cartoon. Here “Miss 1912” dressed in the latest fashion, considers the potential presidential candidates in frames on her desk as she might consider potential husbands. They include Woodrow Wilson, William Howard Taft, Theodore Roosevelt, and Robert LaFollette, with other possible candidates, Uncle Sam looks on with amusement.

The cartoon presents both positive and negative views of women and their political power. “Miss 1912” is thoughtful, and the choice before her, selecting a president, involves the right to vote. It was a power that women in states surrounding Oregon had achieved; cartoonist Murphy suggests that Oregon women will gain that power in the upcoming election of 1912. Yet because the candidates are arrayed as potential husbands it might appear as if “Miss 1912” is simply looking for the most handsome choice (a charge that some opponents made about women voters). Actions in leap year could be considered unusual exceptions rather than rights and obligations.

Without direct comments from readers, it is hard to know just how they received “Leap Year is Coming”.

Like today, editorial cartoons in the suffrage era seized readers’ interest, called on ideas and emotions and were memorable. Both sides of the suffrage campaign used images to advance their cause.

—Kimberly Jensen

Want to read more articles from Oregon suffrage campaigns? Click here

Permalink

November 1911: Southern Oregon’s E.W. Cooper and Wife Want Daughter to Vote

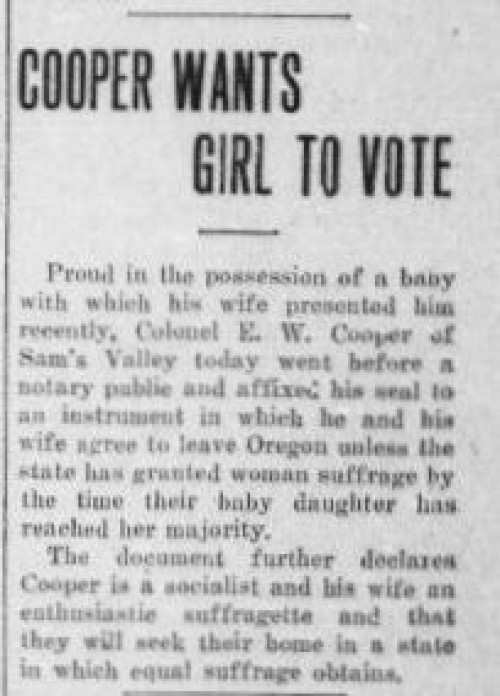

Much of the history of the campaign for votes for women in the state relates to the work of organizations, clubs and associations. But the case of E.W. Cooper and his wife, who lived in Sam’s Valley in Southern Oregon’s Jackson County, provides an example of two individuals taking action to promote woman suffrage.

They would leave the state, they said, if their new daughter could not cast a ballot in Oregon when she reached voting age.

“Proud in the possessions of a baby which his wife presented him recently,” the Medford Mail Tribune reported on November 17, 1911, Colonel E.W. Cooper of Sam’s Valley today went before a notary public and affixed his seal in an instrument in which he and his wife agree to leave Oregon unless the state has granted woman suffrage by the time their baby daughter has reached her majority.

“The document further declares that Cooper is a socialist and his wife an enthusiastic suffragette and that they will seek their home in a state in which equal suffrage obtains.”

“Cooper Wants Girl to Vote,” Medford Mail Tribune, November 17, 1911, 1.

As Rebecca Mead demonstrates in How the Vote Was Won: Woman Suffrage in the Western United States, 1868-1914 (New York: New York University Press, 2004) many members of the Socialist, Progressive and Populist parties embraced woman suffrage as part of their reform vision.

E.W. Cooper and his wife evidently fit this pattern. And they took this innovative step to publicize their commitment to the suffrage cause.

—Kimberly Jensen

Want to read more articles from Oregon suffrage campaigns? Click here

Permalink

October 1911: Medford Mail Tribune Sees Hope for Oregon Woman Suffrage with California Victory

On October 10, 1911 California voters approved Proposition 4 in a special election and women in that state achieved the right to vote.

Oregon suffragists were watching. They had signatures for a November 1912 ballot measure in hand and that past May 1911 had formally launched the 1912 campaign.

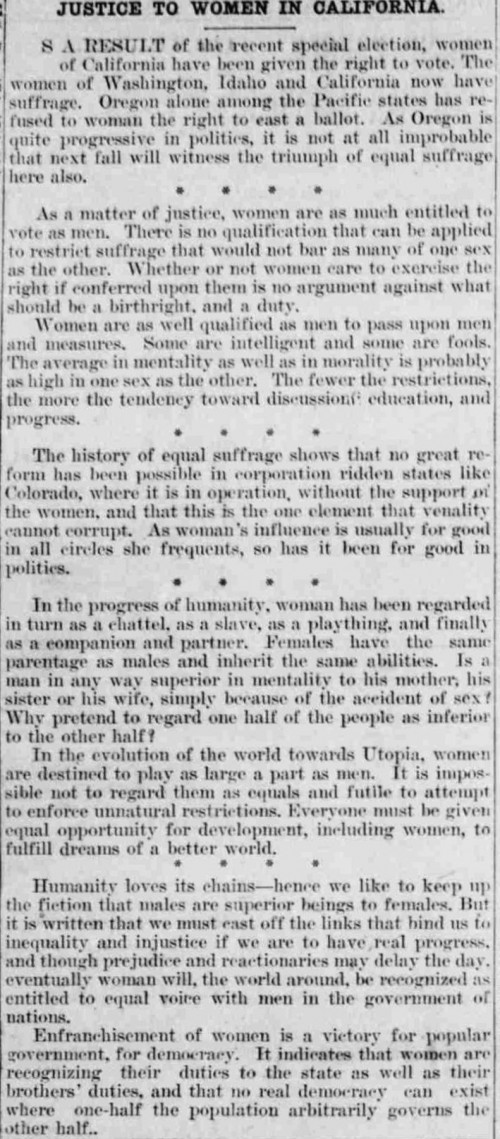

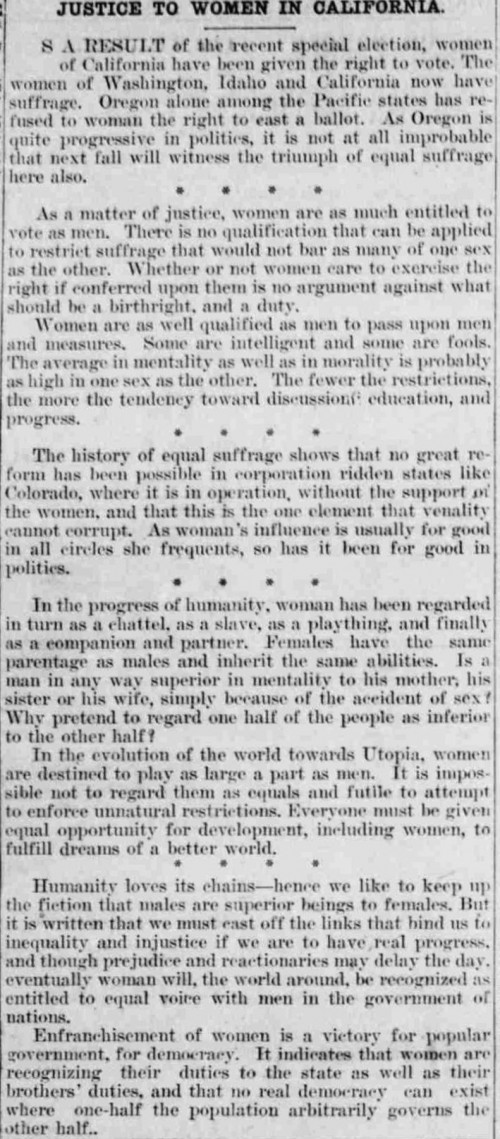

On October 14, 1911 the editors of the Medford Mail Tribune in Southern Oregon published an editorial titled “Justice to Women in California.” They outlined reasons why they felt woman suffrage was just, necessary, and a progressive step toward more complete democracy. The California victory meant that Oregon was surrounded by suffrage states. “Oregon alone among the Pacific states has refused to woman the right to cast a ballot,” they noted. “As Oregon is quite progressive in politics, it is not at all improbable that next fall will witness the triumph of equal suffrage here also.”

The editorial contained many arguments for woman suffrage that supporters would use in the upcoming campaign.

Woman suffrage was a “matter of justice.” It was also a “victory of popular government, for democracy.”

The editors countered the anti-suffrage argument that some women did not want the vote. “Whether or not women care to exercise the right if conferred upon them is no argument against what should be a birthright, and a duty.” And to the argument that women were not ready or able to vote, they responded: “Women are as well qualified as men to pass upon men and measures. Some are intelligent and some are fools. The average in mentality as well as in morality is probably as high in one sex as the other. The fewer the restrictions, the more the tendency toward discussion, education, and progress.

The editors believed in progress and argued that votes for women were a necessary part of that progress.

“In the progress of humanity,” they wrote, “woman has been regarded in turn as a chattel, as a slave, as a plaything, and finally as a companion and partner. Females have the same parentage as males and inherit the same abilities. It a man in any way superior in mentality to his mother, his sister, or his wife, simply because of the accident of sex? Why pretend to regard one half of the people as inferior to the other half?”

“In the evolution of the world towards Utopia,” the editors continued, “women are destined to play as large a part as men . . . Everyone must be given equal opportunity for development, including women, to fulfill dreams of a better world.”

Social inequality was based on the “fiction that males are superior beings to females.” But the editors were confident that change was in the works. Even “though prejudice and reactionaries may delay the day, eventually women will, the world around, be recognized as entitled to equal voice with men in the government of nations.”

“Justice to Women in California,” Medford Mail Tribune, October 14, 1911, 4.

Oregon suffragists must have taken heart in these expressions of support. The California victory strengthened their argument that Oregon was surrounded by progressive states and needed to catch up by providing for woman suffrage.

The Medford Mail Tribune editors’ belief in progress reminds us that the movement for woman suffrage was and is linked to the broad struggle for human rights across the globe: for civic rights, marriage rights, the rights of safety and freedom of expression for all people. It is a struggle in which we continue to be engaged.

—Kimberly Jensen

Want to read more articles from Oregon suffrage campaigns? Click here

Permalink

October 1911: Medford Mail Tribune Sees Hope for Oregon Woman Suffrage with California Victory

On October 10, 1911 California voters approved Proposition 4 in a special election and women in that state achieved the right to vote.

Oregon suffragists were watching. They had signatures for a November 1912 ballot measure in hand and that past May 1911 had formally launched the 1912 campaign.

On October 14, 1911 the editors of the Medford Mail Tribune in Southern Oregon published an editorial titled “Justice to Women in California.” They outlined reasons why they felt it woman suffrage was just, necessary, and a progressive step toward more complete democracy. The California victory meant that Oregon was surrounded by suffrage states. “Oregon alone among the Pacific states has refused to woman the right to cast a ballot,” they noted. “As Oregon is quite progressive in politics, it is not at all improbable that next fall will witness the triumph of equal suffrage here also.”

The editorial contained many arguments for woman suffrage that supporters would use in the upcoming campaign.

Woman suffrage was a “matter of justice.” It was also a “victory of popular government, for democracy.”

The editors countered the anti-suffrage argument that some women did not want the vote. “Whether or not women care to exercise the right if conferred upon them is no argument against what should be a birthright, and a duty.” And to the argument that women were not ready or able to vote, they countered: “Women are as well qualified as men to pass upon men and measures. Some are intelligent and some are fools. The average in mentality as well as in morality is probably as high in one sex as the other. The fewer the restrictions, the more the tendency toward discussion, education, and progress.

The editors believed in progress and argued that votes for women were a necessary part of that progress.

“In the progress of humanity,” they wrote, “woman has been regarded in turn as a chattel, as a slave, as a plaything, and finally as a companion and partner. Females have the same parentage as males and inherit the same abilities. It a man in any way superior in mentality to his mother, his sister, or his wife, simply because of the accident of sex? Why pretend to regard one half of the people as inferior to the other half?”

“In the evolution of the world towards Utopia,” the editors continued, “women are destined to play as large a part as men . . . Everyone must be given equal opportunity for development, including women, to fulfill dreams of a better world.”

Social inequality was based on the “fiction that males are superior beings to females.” But the editors were confident that change was in the works. Even “though prejudice and reactionaries may delay the day, eventually women will, the world around, be recognized as entitled to equal voice with men in the government of nations.”

“Justice to Women in California,” Medford Mail Tribune, October 14, 1911, 4.

Oregon suffragists must have taken heart in these expressions of support. The California victory strengthened their argument that Oregon was surrounded by progressive states and needed to catch up by providing for woman suffrage.

The Medford Mail Tribune editors’ belief in progress reminds us that the movement for woman suffrage was and is linked to the broad struggle for human rights across the globe: for civic rights, marriage rights, the rights of safety and freedom of expression for all people. It is a struggle in which we continue to be engaged.

—Kimberly Jensen

Want to read more articles from Oregon suffrage campaigns? Click here

Permalink